ICCT – Exploring the potential environmental impacts of new renewable diesel capacity on oil and fat markets in the United States.

The production of renewable diesel by hydrotreating oils and fats has expanded rapidly around the world over the past decade. Unlike conventional biodiesel, renewable diesel is chemically similar enough to fossil diesel that it can be used in existing diesel engines with no blend limit. The process can produce renewable jet fuel as a co-product with minor modifications.

The United States currently supports renewable diesel supply through the federal Renewable Fuel Standard, a biomass-based diesel blenders tax credit, and state level policies such as the California Low Carbon Fuel Standard and Oregon Clean Fuels Program.

Based on recent credit values under these programs, this stack of policy support could be worth $4 per gallon for waste-oil-based renewable diesel supplied in California. The U.S. currently has about 800 million gallons of renewable diesel production capacity, and in 2020 produced about 500 million gallons.

🔥 What about we co-host a webinar? Let's educate, captivate, and convert the biofuels economy!

Biofuels Central is the global go-to online magazine for the biofuel market, we can help you host impactful webinars that become a global reference on your topic and are an evergreen source of leads. Click here to request more details

The generous policy environment for renewable diesel has inspired a cascade of announcements of new projects, including new standalone facilities, conversions of existing refinery units and co-processing with fossil fuels at existing refineries.

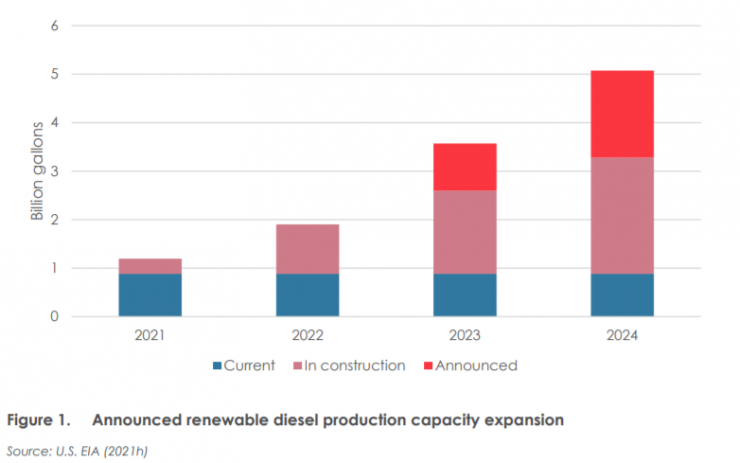

The Energy Information Administration reports that if all of these announced plans come to fruition renewable diesel production capacity in the U.S. would increase fivefold by 2024, from just under 1 billion gallon a year to more than 5 billion gallons per year (Figure 1). Running all of those potential facilities at full capacity would create 17 million metric tons of additional demand for oils and fats.

If this capacity expansion could be delivered, it would represent a massive shift in the U.S. biofuel industry. Already the growth of renewable diesel production is impacting feedstock markets, with many analysts identifying growth in renewable diesel as a factor contributing to recent record soy oil prices. It is difficult to see how the millions of metric tons of vegetable oil that would be needed to supply a 5 billion gallons a year industry could be delivered.

Predicted increases in domestic soy oil production could support perhaps another 300 million gallons of production, and increased utilization of waste and residual oils another 150 million gallons. Beyond this, increasing production would mean either dramatic unforeseen expansion of domestic soy and canola area, dramatic increases in canola and palm oil imports, or massive displacement of feedstock from other uses (or a combination of the three).

Domestic biodiesel production is likely to be strongly impacted, with waste oils and fats in particular diverted to renewable diesel production for supply to the West Coast.

In practice, it seems highly unlikely that the full announced capacity expansion will be delivered. Limits on feedstock availability and limits on the support available for renewable diesel production from the RFS and other policies mean that the market will not support a 5 billion gallons industry as soon as 2024 (if ever). We expect that the next five years will see some projects delayed or cancelled, and some running far below nameplate capacity.

Even if only a half or a third of the announced capacity is delivered it still represents a massive increase in feedstock demand. There is a high risk that increased U.S. renewable diesel production will indirectly drive expansion of palm oil in Southeast Asia, where the palm oil industry is still endemically associated with deforestation and peat destruction.

Consuming millions of metric tons of additional vegetable oil could cause tens of thousands of hectares of deforestation.

In setting recent volume mandates for the RFS, the EPA has stated that it is reluctant to mandate excessive growth in advanced biofuel requirements because of the risk that delivering more and more biomass-based diesel could cause market distortions and lead to CO2 emissions from land use change.

The current ramping up of the renewable diesel industry is an attempt to deliver that excessive growth, and there seems to be a very great risk that those undesirable market distortions will be realized.

For states with low carbon fuel standards and similar programs, there is a question to be answered about whether unlimited growth in local renewable diesel supply is the best way to deliver on climate goals.

If a major outcome of these policies is to suck in resources that would otherwise be supplied as biodiesel elsewhere, and thereby undermine the existing biodiesel business, that has little net climate benefit.

Similarly, if the rapidity of vegetable oil demand increases leads to social damage through high food prices and to ILUC emissions as oil palm expands to compensate, that also will have little net climate benefit.

It may be appropriate for state programs to consider limiting the contribution from renewable diesel. More generally, the growth in vegetable oil hydrotreating as a biofuel pathway risks distracting investment from cellulosic biofuel technologies that are still not in wide operation at commercial scale, but that in the long-term could be more scalable, more sustainable, and cheaper.

Access the full report following the link below.

Animal, vegetable or mineral (oil), January 2022